Above: Salvador Dali’s persistence of time

Imagine that you are enveloped in darkness. So dark, that you cannot see the hand in front of your face. There is no day, and there is no night. There is no sound. You are utterly alone, and you are trapped. Hours, days, weeks, months, years might have passed…you have lost all track of time. This is the reality for hundreds of Canadians in Solitary Confinement, at this very moment.

The actual number of prisoners in Solitary Confinement is difficult to determine, in part because we have different sets of data for federal and provincial prisons, respectively. The legal term for solitary confinement is segregation. Unfortunately, this basic semantic duality has given rise to a variety of euphemisms–like Disciplinary segregation, Administrative segregation, Isolated confinement—which make it difficult to tally the actual numbers of people in Solitary Confinement. It also allows correctional personnel to get around the rules. For example, Canadian law states that prisoners in disciplinary segregation must be released after 30 days… but if you call it administrative segregation, no such law applies.

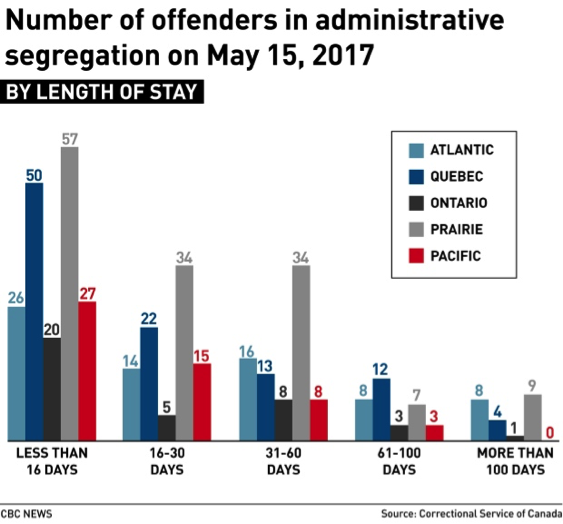

Here are the numbers that CSC gave the CBC for one type of solitary confinement, administrative segregation.

The experiential reality is that people in Solitary Confinement, regardless of what you call it, or why and how they came to be there–are locked in closed cells for 22-24 hours a day, virtually without human contact, for periods of time ranging from days to decades. Some additional definitions:

Isolated confinement is synonymous with solitary confinement. Other synonyms are restricted housing; security housing, restricted communication management…

Disciplinary segregation is solitary confinement imposed as a punishment for inmates who break the rules.

Administrative segregation also known as involuntary protective custody, is solitary confinement for prisoners who are deemed a risk to the safety of other inmates or prison staff. In the bizarre, one-flew-over-the-cuckoo’s-nest world of Canada’s prisons, prisoners may even request this for their own protection… or so claims CSC.

Note that Rule 45 of the UN Mandela Rules states that:

Solitary confinement shall be used only in exceptional cases as a last resort, for as short a time as possible and subject to independent review, and only pursuant to the authorization by a competent authority.

This definition obviously disallows widely used forms of solitary confinement for convenience, such as so-called administrative segregation, (which is perhaps why they renamed it).

Human rights groups challenge the law, and win a short-lived victory

In January 2015, the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA) and the John Howard Society of Canada took the federal government to court, saying that the sections of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) that allow for indefinite solitary confinement (referred to as “administrative segregation” in the legislation) violate Section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

On January 17, 2018, the B.C. Supreme Court agreed. In the Court proceedings, the Crown had argued that Solitary Confinement was reasonable and necessary, but Justice Peter Leask accepted the BBCLA’s contention that solitary confinement is cruel, inhumane, and can lead to severe psychological trauma. The judge noted that the use of solitary confinement disproportionately harms Indigenous women and people with mental illness. He gave authorities a year to make changes, including introducing an appeals process for prisoners put in extended solitary confinement.

The BC court case came on the heels of a similar case, this one by the Ontario-based Canadian Civil Liberties Association, which was heard in September 2017, with judgement rendered in December 2017. However, although the CCLA judge, Chief Justice Marrocco of the Ontario Superior Court, found that Canada had indeed violated prisoners’ Charter rights to freedom, his judgement did not recognize segregation as cruel and unusual punishment, and accordingly the CCLA has filed an appeal.

Stalling

The BCCLA and John Howard society did not get to relish their victory for long. In February 2018, in a surprising turn of events, the federal government announced that it was appealing the B.C. court decision, arguing that it needs clarity on the issue from the courts. How ironic that CSC, which has traditionally shrouded its practices in secrecy, and obfuscated its documentation, should suddenly become the ardent champion of “clarity”! (Brings to mind Justin Trudeau’s dumbfounding excuse for nixing Proportional representation, an electoral reform towards consensus-based government, on grounds of “no consensus.”)

Meanwhile, Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale’s proposed legislation to set a 15-day limit on the use of “administrative segregation” and to implement a system of independent oversight, has not moved since it was tabled in summer of 2017. Goodale’s reform would satisfy the minimum set by the United Nations Committee Against Torture, (which has also called for the complete prohibition of solitary confinement). Fifteen days is an improvement, but many would (and do) argue that torture of a shorter duration is still torture.

Prisons are the new residential schools

Ojibwe youth Adam Capay fits the profile of the demographic hardest hit by Correction Services Canada’s solitary confinement practices. Capay was only 19 when he was first arrested on minor charges. Despite his age, he was sent to adult jail, where in 2012, an altercation resulted in Capay being charged with the death of Sherman Quisses, of Neskantaga First Nation while both men were in custody. Capay spent five and a half years (53 consecutive months) in solitary confinement. Perhaps because of extensive media coverage, Capay is now out of solitary, and awaiting a new trial. A Council of Canadians group has started a fundraiser for Capay so his family can attend the proceedings.

What lies ahead

At least these two court cases, and Judge Leask’s decision, have shed some light into the bleak practice of placing people in solitary confinement. And spurred some action– for example, there is the previously mentioned CCLA appeal, and on February 2, 2018, Saskatchewan lawyer Tony Merchant launched two class-action lawsuits claiming the federal and provincial governments are breaching the charter rights of correctional inmates by keeping them in segregation for “administrative” reasons.

The need for reform is urgent. Somewhere, at this very moment, human beings in solitary confinement are struggling with their sanity, struggling with despair, profoundly alone… alive, yes, but suspecting that, as far as Canadian society is concerned, they have already died.

Regarding the paragraph “Prisons are the new residential schools,” above, there is fantastic news today: Adam Capay was finally freed. He spent 4 1/2 years in solitary confinement. 🙁

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-judge-issues-stay-in-adam-capay-case/